In Bren’s telling, some of the same forces that brought them to Manhattan led to the end of the Barbizon as they knew it-and to the New York City that we know today. More than a biography of a building, the book is an absorbing history of labor and women’s rights in one of the country’s largest cities, and also of the places that those women left behind to chase their dreams.

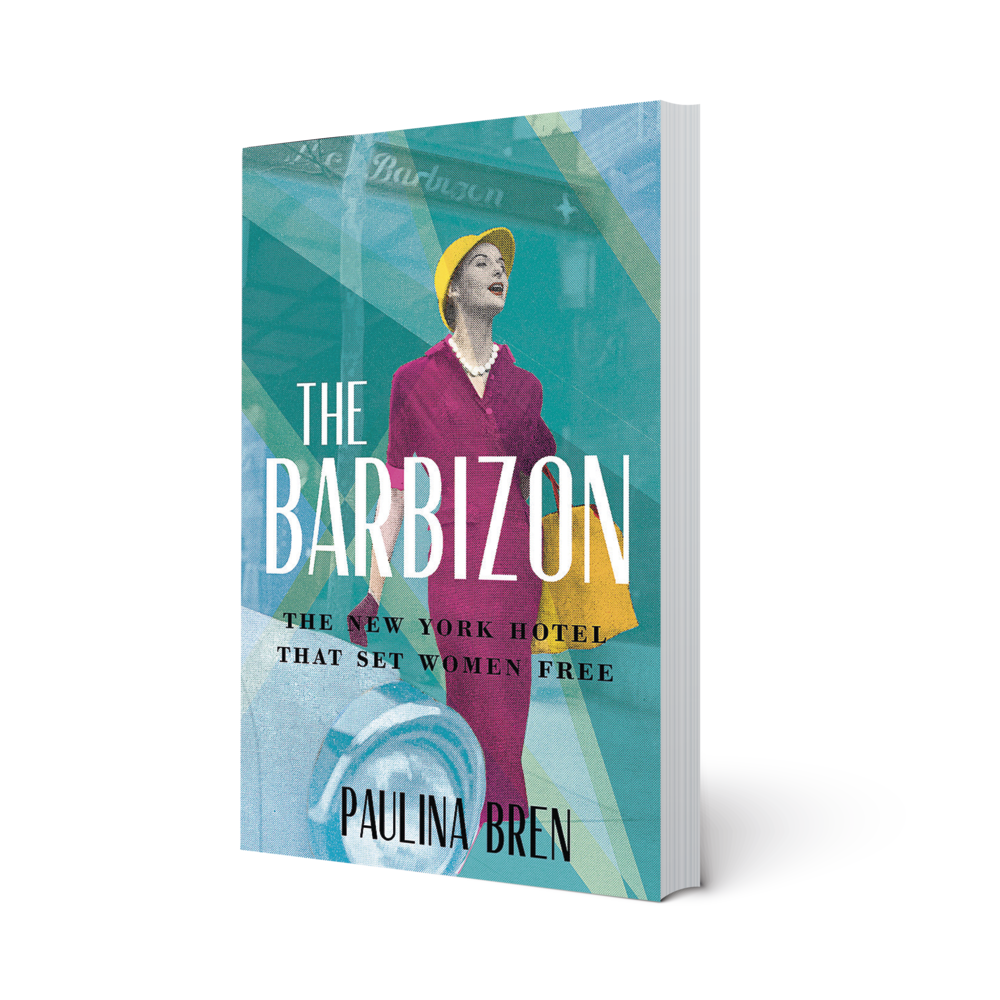

The historian Paulina Bren, in her new book, “The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free” (Simon & Schuster), chronicles the experiences of these women, and of some of the hundreds of thousands of others like them, who stayed in the hotel.

Actresses like Grace Kelly, Liza Minnelli, Phylicia Rashad, and Cybill Shepherd took their beauty sleep there, walking the same halls as writers like Sylvia Plath and Peggy Noonan and riding the same elevators as the future First Lady Nancy Reagan. The subject of films and of novels, the Barbizon was also a mainstay of the society pages. Some of them opened in the late nineteenth century, though most were built around the time of the First World War few had the cultural cachet of the Barbizon. Most of these hotels were curiosities of long-since-reformed real-estate regulations, exempt from building-height restrictions and from fire-safety regulations, so long as they did not have kitchens in their guest rooms. New York City once had more than a hundred residential hotels, places like the Algonquin, where Dorothy Parker and James Thurber held court by day and laid their heads at night and the Carlyle, where President Kennedy kept an apartment and the Plaza, whose most famous resident was fictional, the six-year-old Eloise, who lived in her “pink, pink, pink” room.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)